Carl-Johann Vallgren

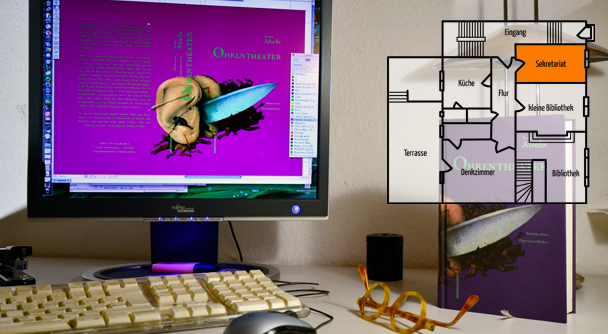

Our volume »Young European Narrators«, edited in both languages, German and English, contains Carl-Johan Vallgren's natrration »Documents Concerning the Gambler Rubachov«.

Carl-Johan Vallgren is born in Sweden in 1964.

In his literary works Vallgren concentrates on longer nar-ration – and it stands for the excellence of his novels that they have been published in close succession at the inter-nationally well-known swedish publishing house for literature „Bonniers Förlag“.

Vallgren, at first sight, seems to use rather traditional principles in composition and structuring of his narrations. For instance there is the book he is writing at present (»För Herr Bachmanns broschyr« / »For Mr Bachmann’s booklet«) that is given the classical form of a novel in letters; and also the novel »Documents Concerning the Gambler Rubashov« might have been written in the older days in which its hero is playing his final game: at the end of the 19. Century.

But all these traditional aspects are nothing else but the mimikry of a crafty novelist. For it is a characteristic of Carl-Johan Vallgren’s narrations that he always is on the side of his characters; always he is – to speak in terms of last century’s literature – a Dostojewskij: No matter how many devils are behind of one of the heros and no matter how diabolic one turns out to be, Vallgren is their narrating lawyer. However deap a Rubashov falls or is made falling by his inventor, however bad a situation or character is – lovingly Carl-Johan Vallgren stands up for him.

In our volume »Young European Narrators« we present the beginning of his novel »Documents Concerning The Gambler Rubashov«.

SCA Young European Narrators

5 Narrations

- 202 pages

- hardcover

- with ribbon and jacket

- 20 Euros

- Introduction by Hilmar Hoffmann

SCA

Contents

Documents Concerning the Gambler Rubashov

Beginning of a novel by Carl-Johan Vallgren

The Inner Island

Short prose by Katrin Heinau

The Other Man

Short story by Scott Bradfield

Eternity Captured by the Second

44 poetical episodes by Thomas Schwab

Nur Hereinspaziert!…

An Author’s life narrated by Dominique Ponçet

Introduction by Hilmar Hoffmann

Europe as a narrative: Would this not be a good idea? Were this the case, defining and discussing Europe’s borders would become superfluous. Europe would then not end at the foot of the Ural mountains, but quite simply there where its stories are no longer heard, read, or understood. It would be pointless to define Europe’s identity because with the stories (including our own deeds), Europe would become a never-ending story, an open narrative. To be able to tell stories is the prerequisite for being able to give the relationship to reality a literary form.

Basically this is the oldest understanding of Europe. Only if, and as long as it remains a story with an open end, will the continent remain alive, because the people see themselves, their wishes and hopes reflected in it.

Such a Europe cannot be an end in itself. The „Narrative Europe“ finds its legitimation in the quality of the life perspectives of its citizens, in the motivating richness of its Arts, in its cultural discourse and in the lasting contribution to a world that is at peace and capable of a future.

Europe will gain this quality only if it does not sell out on its own standards. The better periods of its history enabled the development of what is known as Europe’s cultural heritage—its contribution to today’s world culture. Today this heritage is world heritage and Europe should not stagnate by refering to the common cultural traditions. No, instead of „museumising“ the values, these have to be developed further in order to signalise the fact that the European claim to a humane standard of living is possible in times of Globalisation and the „Crisis of Modernism“.

It is therefore necessary that the extreme differences be-tween poor and rich no longer be tolerated. As long as Europe continues to accept poverty and destitution amongst its citizens as a necessary evil in the attempt to stimulate the economy, critical voices will continue to oppose this direction in an attempt to protect the human dignity. The same applies to the supression of minorities and acceptance of intolerance, if it gives in to organised crime with its humane standards of law.

What is acknowledged by the big Narrative as being the most important goals and qualities of the European Unification in the post war period, is the burning desire of the younger generation to be able to make the bloody wars of the nationstates a thing of the past.

In the same way as the Europeanisation of the German Question was an attempt to keep a tight rein on German militarism and to tame German revanchism, so will territorial wars become obsolete in a unified Europe—at least as long as justice is secured for its citizens (in this, let Jugoslavia serve as a warning), outside interference is warded off, and their integrity protected by acceptance of central institutions.

Unity amid the diversity should be of central importance. Europe should be a territory of tolerated, approved, positive evaluated variety, and—why not—show others that such politics of welfare is good for the people.

Paragraph 1 of the much quoted article 128 of the Maastrich Agreement states: „The community is making its contribution to the cultural development of its member states by safeguarding their national and regional variety whilst emphasizing the common cultural heritage.“ The Community will make this possible with „supportive measures under exclusion of any harmonisation of the legal and administrative regulations of the member communities“, as it is stated in paragraph 5. This is neither a sad compromise nor it is an empty phrase—it is political, structural goal. In this lies one of the important prospects for the future and standing of Europe.

The many voices of Europe increase the likelihood that certain personalities take an active part in contributing to Europe’s future. Being able to make individual demands

is therefore not an obstacle, but a prerequisite for a uni-

fied Europe. One particular advantage of the „European variety“ is the fact that all attempts at homogenisation can be rejected. This programme of unity amongst diversity cannot reduce itself on a higher level to a homogenous block, that much the same as once the nationstates, now compete with similar closed unity. For this reason alone I am sceptical of the strong incantation of „European common interests“: those who plea for this are those who would much rather fence themselves off from ohters. But the right perspective is not the fencing off, it is openness, as is pro-duced by quality of life and politics.

It certainly cannot be the European goal to substitute those age-old European enemies Germany versus France with similar anachronistic enmities, such as Europe and the Islamic or Confucian world. Europe is only attractive as a global partner if it consciously works at finding global structures which enable us to live with a mutual acceptance of differences and help us to accept this „being different“

as a productive factor. Europe will become an open-ended narrative if it reorganizes itself in such a way as to enable old structures to give way to new and better ones.

A narrative is not a narrative without the narrative voice or a storyteller. As history has shown, storytellers can work miracles. The German ethnologist, Leo Frobenius once told the miraculous story of an African storyteller called Far-Limas who once, in the kingdom of Sudan, saved his own and his King’s life by telling „stories that were as sweet as honey and intoxication as hashish“. By telling these stories he prevented the wisemen of the country from watching the stars, with the result that they could not determine the correct time to make the human sacrifice…

Those storytellers who tell us about the history of Europe keep this continent alive. They create vital images, images which we all can relate to. These storytellers should be encouraged and supported so that they can enrich our society with their visions and insights: imagination, provocation and inspiration, such important contributions to the big European narrative. Our fears and worries, our hopes and wishes, our future depends on this input.

Hilmar Hoffmann

(former president of Goethe Institute)